Da Vinci in a flash

A sensorial portrait of the artist who transformed human curiosity into art, science, and eternity

Talking about Leonardo da Vinci is to revisit the exact point at which the Renaissance ceases to be just a historical period and becomes a way of seeing the world. His work, studied in museums, universities, and laboratories, remains one of the most sought-after pillars in the history of art, whether for the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, the Vitruvian Man, or his visionary inventions. In a time when we consume images at an almost instant speed, returning to Leonardo in “flashes” is to discover that his impact endures precisely because it never relied on haste, but on depth.

The visual journey inevitably begins with the most recognizable icon in the history of art: the Mona Lisa. Her enigmatic smile has become a global cultural phenomenon, studied by historians, scientists, and psychologists. The sfumato technique creates an atmospheric effect that dissolves outlines and brings the painting closer to a real breath. It’s no wonder that the portrait remains one of the most researched works online — not only for its mystery, but for the way Leonardo managed to capture humanity, ambiguity, and introspection in a single gaze.

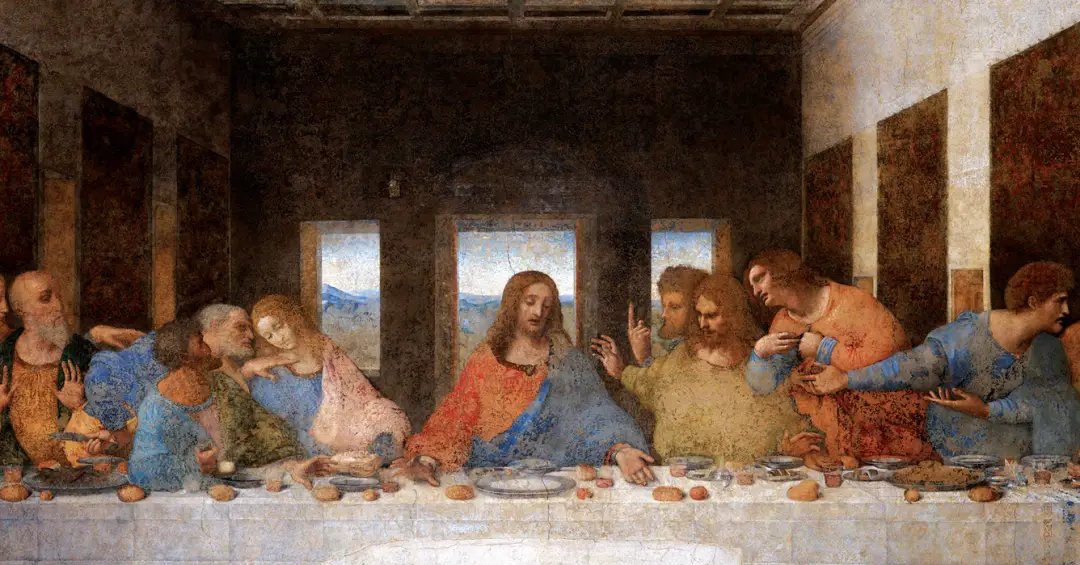

If the Mona Lisa reveals introspection, The Last Supper reveals drama. The scene is recognized as a landmark of the High Renaissance and has become a mandatory reference for those researching perspective, composition, and visual narrative. Leonardo reconfigures the biblical moment as a choreographed explosion of human emotions: astonishment, doubt, indignation, fragility.

The line of the table functions almost like a ruler of time, while the central perspective guides the viewer’s gaze directly to Christ. It is a work that combines architecture, psychology, and visual rhythm, and has been exhaustively studied by institutions such as the National Gallery, the Encyclopedia Britannica, and countless historians who see in it a watershed moment in the way of storytelling through painting.

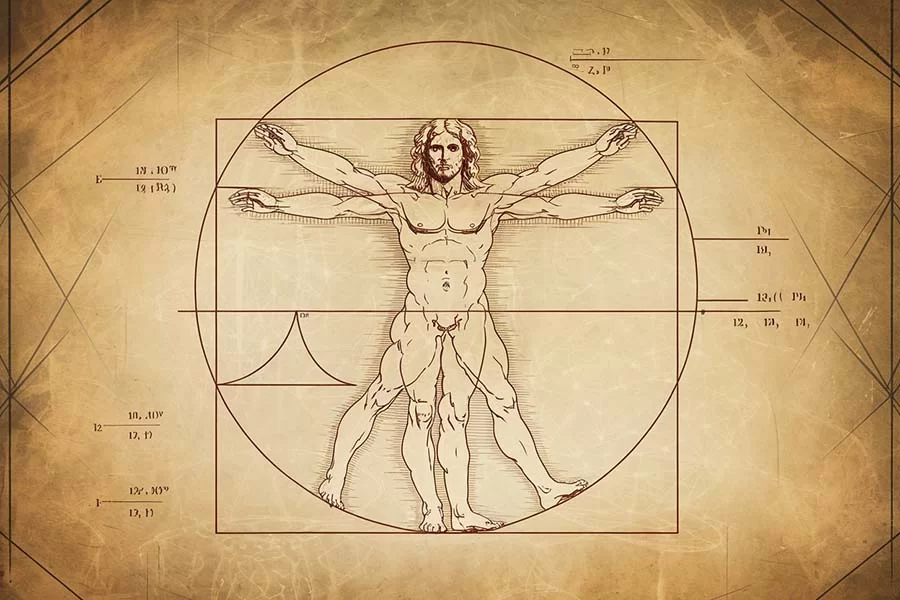

The Vitruvian Man, his other work, is the ideal link to explain Leonardo’s intellectual dimension. The drawing, now widely reproduced and cited in scientific studies, represents the perfect convergence of proportion, anatomy, and cosmic vision. Based on the writings of Vitruvius, Leonardo proposes that the human body is both measure and metaphor. Studies published in sources such as the WEA, Wikipedia, and The Art Story reinforce that the Vitruvian Man has become the ultimate symbol of the union between art and science, and perhaps the greatest example of the artist’s restless mind.

Leonardo’s sensitivity to portraits goes beyond physical features. In works such as the Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci and The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, every gesture, every tilt of the face, and every detail seem laden with inner life. Critics and historians point out, in analyses found on platforms such as SimplyKalaa and international museums, that Leonardo brought portraiture closer to the psychological field. He recorded not only faces but also states of mind. It is this silent depth that makes his works remain so relevant in the contemporary imagination.

At the end of his career, Leonardo created works that seem to condense mystery and introspection. Saint John the Baptist, often considered his last great painting, reveals an almost enigmatic spirituality. The discreet smile, the pointing hand, the intense play between light and shadow: everything seems to suggest something that escapes the literal. Research found in sources such as WIRED and The Art Story reinforces how this work consolidates the metaphysical atmosphere that marks Leonardo’s final phase, a moment when art, faith, and philosophy meet inseparably.

It is impossible to understand Leonardo solely as a painter. He was an anatomist, engineer, scientist, relentless observer. His studies on hydraulics, his flying machines, his investigations into mechanics and human anatomy are part of a repertoire that expanded the boundaries of knowledge in the fifteenth century. Sources such as Encyclopedia Britannica, WEA, and various academic analyses show that he anticipated concepts that would only be developed centuries later. For Leonardo, art and science were parts of the same impulse: the desire to understand the world.

In an accelerated world, revisiting Leonardo da Vinci in flashes, frames, or quick cuts is an interesting contrast: his genius does not fit into a few seconds, yet it curiously remains intact even when translated into contemporary formats.

His impact does not depend on exposure time but on the depth of gaze. And perhaps that is why in each work, from the Mona Lisa to the Salvator Mundi, from the Last Supper to the Vitruvian Man, we still find questions, illuminations, ideas, and connections that continue to dialogue with the beholder. Leonardo endures because his work does not seek quick answers: it offers the eternal possibility of discovery.