Deciphering the Military Alphabet and Morse Code

Kaia Gerber nous présente ses lectures les plus formatrices, de L'Année de la pensée magique de Joan Didion à Just Kids de Patti Smith

Before screens, instant messaging apps and devices capable of translating voices to text existed, humanity was already seeking ways to communicate with precision. These were times when any noise, technical failure or weather interference could mean the loss of an important message.

It is in this scenario that two systems emerged that crossed wars, oceans, borders and decades: the NATO phonetic alphabet and Morse code. Both function as parallel languages, created to ensure absolute clarity when everything around is unstable. Today, even in a hyperconnected world, these two structures remain essential in air, sea, military and emergency operations, as well as surviving in the collective imagination as symbols of human ingenuity.

The phonetic alphabet, or NATO Phonetic Alphabet, was born out of the need to turn isolated letters into clear, internationally recognizable words. In radio transmissions, especially in environments with intense noise, wind, static or mechanical interference, letters like B, D, P and T sound almost identical. To avoid errors that could compromise entire operations, a list of words was created to represent each letter unequivocally. Thus came Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo and Foxtrot, all the way to Zulu. Each term was carefully chosen for its universal diction, capable of crossing different accents and languages without losing clarity.

Between the chaos of frequencies, Morse remains as the line that guides meaning.

The system's inteligence

This system quickly became the standard for aviation, military operations, maritime navigation, police services and emergency communication. In a cockpit, the phrase Hotel Lima Three Seven is not poetry, but a code representing HL37. On a ship, Foxtrot Sierra can convey a strategic message. For rescue teams, saying Victor Alpha can mean a vital instruction. The structure works like a language within a language, allowing people in different parts of the world to speak the same operational tongue, even without sharing the same everyday vocabulary.

The logic behind this alphabet goes beyond technique. It functions as a silent global agreement that communication must be exact when lives and operations depend on it. A single word spoken clearly can cross storms, distances and noises that would confuse any isolated letter. That is why, even with advanced digital radio, satellite and voice encoder technology, the phonetic alphabet remains relevant. It does not require complex devices, only vocal precision and common understanding.

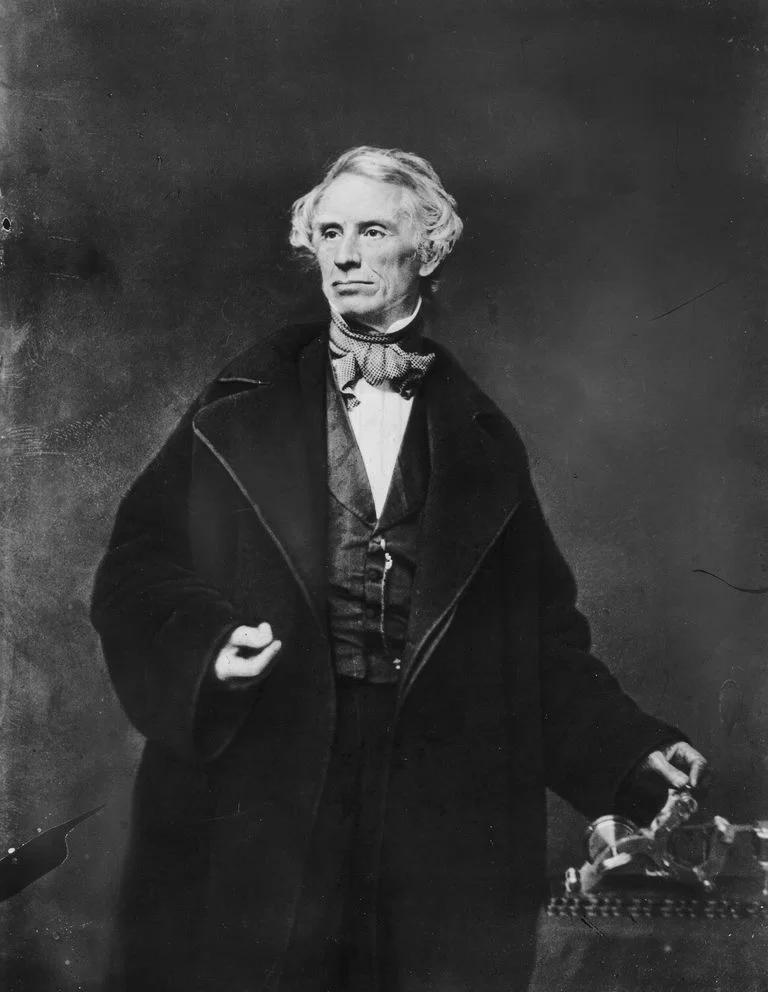

While the phonetic alphabet dominates spoken communication, Morse code represents the visual and auditory equivalent of that precision. Created by Samuel Morse in the 1830s, it was initially conceived for telegraphy, turning electrical pulses into dots and dashes that formed words, sentences and entire messages. Morse quickly spread, becoming essential in maritime communications, military transmissions and strategic operations during wars. The famous SOS, composed of three dots, three dashes and three dots, crossed centuries as a kind of universal language for danger situations.

Morse stands out for its ingenious simplicity. It does not rely on voice, language fluency or proximity. It can be transmitted by light, sound, vibration, knocks and even improvised reflections. That is why it remains today as an important skill in amateur radio and emergency operations. When all technologies fail, dots and dashes become the last possible language. What may seem rudimentary is, in fact, an extremely resilient code, capable of surviving even where no other instrument works.

The comparison between past and present reveals the strength of these two systems. The telegraph that dominated 19th-century communications contrasts with the digital radio flying inside contemporary aircraft and ships. Nonetheless, the logic behind Morse code remains essential. In a technological world, there is something almost poetic about the continuity of this system, as if reminding us that all human communication is based on rhythm, clarity and intention.

In the cultural universe, these codes have also left their marks. Expressions like Bravo Zulu, traditionally used by the Navy as a way to say “excellent work,” migrated to movies, series and everyday conversations. Terms like Checkpoint Charlie became icons of Cold War history. And the expression Zulu Time, used to standardize military time zones, today is present in pilots’ routines around the world. The phonetic alphabet and Morse code transcended technique, becoming part of collective cultural memory.

There is a playful and contemporary aspect that also runs through these systems. Writing HELLO as Hotel Echo Lima Lima Oscar has become a fun challenge, as has translating simple words into dots and dashes. On social media, code pages, interactive videos and even educational games explore this universe. This play, however, reveals something larger: even in a world dominated by the speed of digital messages, we feel fascination for languages that demand attention, decoding and a touch of mystery.

Despite emerging in rigorous and formal contexts, the phonetic alphabet and Morse code carry a delicate harmony between simplicity and complexity. They are systems that transcend time because they respond to a fundamental human need: to transmit information clearly, even when nothing helps. They remind us that communication is not just technical, but also a way to connect, coordinate and create stories that cross distances.

Today, understanding these codes is a way to dive into the history of communications and, at the same time, recognize human creativity in its most practical form. They are tools that reinvented the way we speak and listen in extreme scenarios, but also symbols that remain alive in the global imagination. On planes, ships, radio stations, rescue centers and even in cultural curiosity collections, Alfa, Bravo, Charlie and the dots and dashes of Morse continue echoing.

In the end, there is something profoundly human in these two systems. They arose in moments of need but survived because they carry clarity, rhythm, simplicity and meaning. And when a message needs to be understood without margin for error, just remember that some of the most powerful languages ever invented are made up of universal words and small signs that say much more than they seem.