The history of the middle finger

A cultural journey of a gesture that has crossed empires, taboos, and centuries of irreverence

Throughout human history, few gestures have been as enduring, as recognizable, and as universally charged with attitude as the famous middle finger. Today it circulates among memes, protests, films, music, pop culture, and situations of pure sarcasm, but its trajectory is much older and much more complex than it appears. The gesture has been an insult, a symbolic weapon, theatrical satire, a political sign, and also a mechanism of humor. To understand why it remains so present, it is necessary to return to the civilizations that shaped the first chapters of this story.

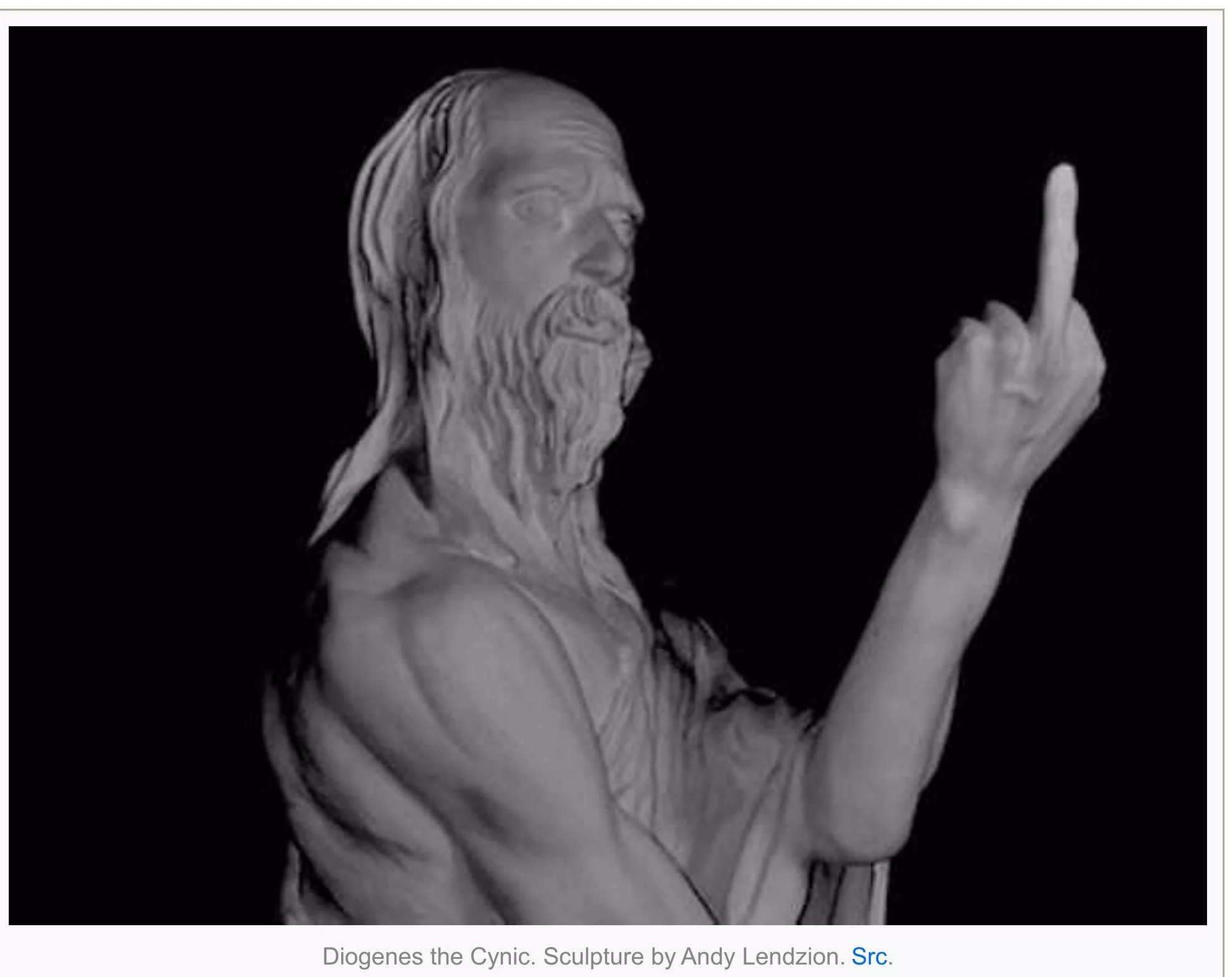

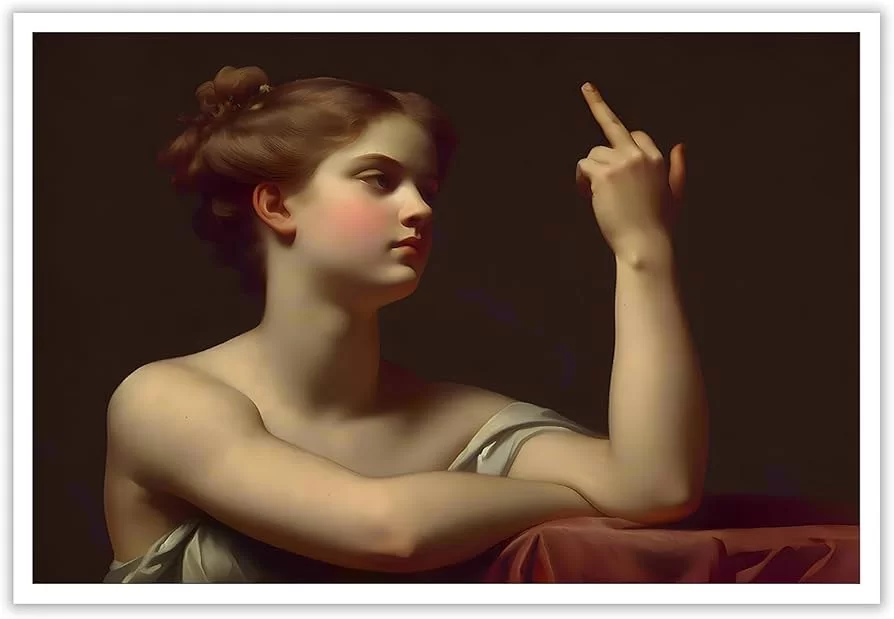

In Ancient Greece, the middle finger already existed and was already loaded with intent. Called katapygon, it was considered an offensive, suggestive, and explicitly provocative gesture, used to insult, mock, or reduce another to ridicule. It appeared in theatrical plays and in political satires, especially in Aristophanes’ comedies, which spared no irreverence. As unbelievable as it may seem, this gesture we now associate with modern rebellion was, even then, a very direct form of communication: the kind of gesture that made it clear the conversation had taken a decidedly undiplomatic turn.

Since its beginning, the gesture showed that humor and insolence walk hand in hand in human history.

The gesture that found its style in Roman hands

Centuries later, the Roman Empire adopted the gesture and gave it a name that endured in historical manuscripts: digitus impudicus, the shameless finger. There, it gained a new layer of meaning. It was offensive, but also theatrical. Soldiers used it to provoke adversaries, actors incorporated it into comedic scenes, and poets mentioned it in satirical verses. The Romans possessed a singular ability to turn body language into a political and social symbol, and the middle finger functioned as a tool of affront and irreverence. In Rome, insults followed method, rhythm, and a particular style.

With the onset of the Middle Ages, much of Greco-Roman popular culture was transformed or suppressed, and the middle finger virtually disappears from the period’s historical references. The Catholic Church, with its strong influence over social conduct, possibly viewed the gesture as indecorous or morally improper. Another possibility is that different regions of Europe developed their own local gestures, which replaced the middle finger as a form of insult. Whatever the reason, this chapter of history is marked by silence. The gesture, which had been so present in antiquity, simply dissolves in the medieval social landscape.

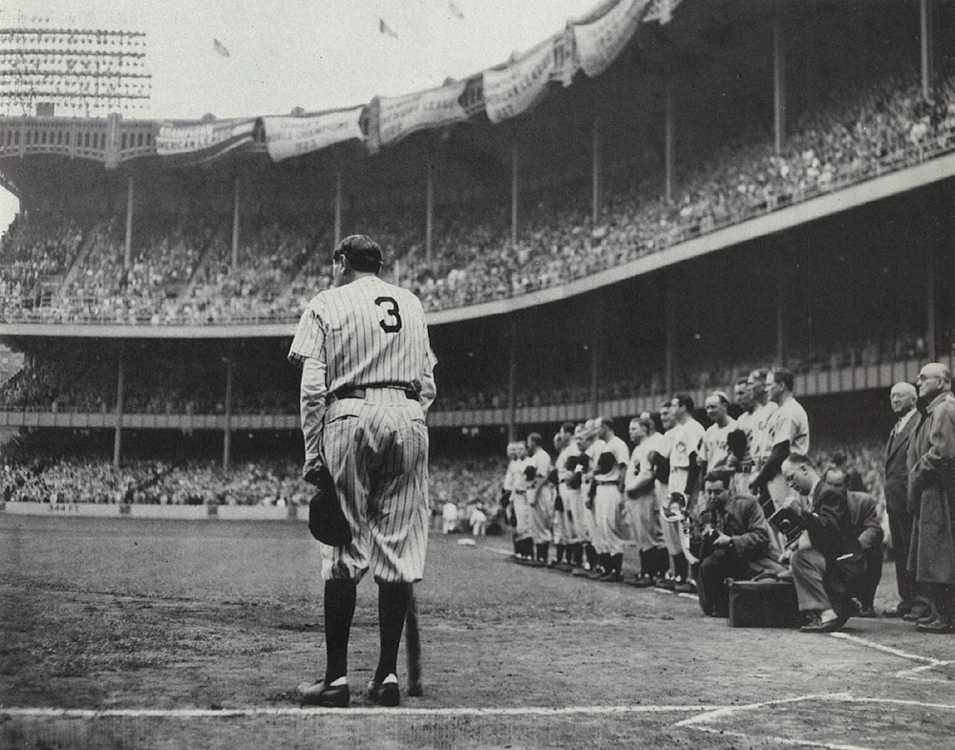

The reappearance of the middle finger happens centuries later, and in a curious way. In 19th-century United States, it resurfaces in a sports context. The first known photograph of the gesture was captured in 1886, showing a Boston baseball player making the gesture toward a rival team. The image reveals that the gesture had returned to the public sphere spontaneously, perhaps influenced by European immigrants or simply reinvented as sports provocation. From there, it began its modern climb into the collective imagination.

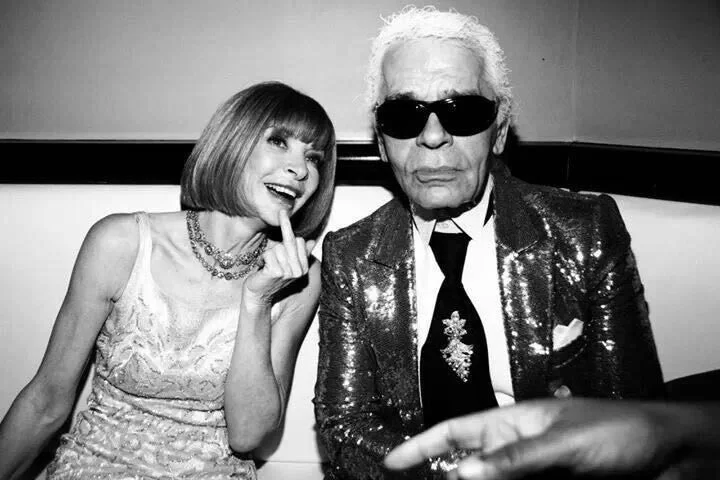

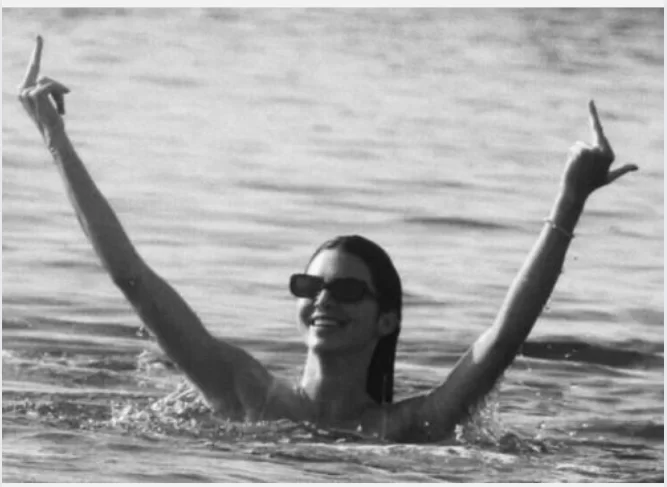

In the 20th century, the middle finger finds its definitive reinvention. The punk movement, countercultural movements, artistic performances, and political demonstrations adopted the gesture as a symbol of anti-establishment energy, sarcasm, and resistance. It became a visual response to express dissent, indignation, or scorn. Its strength lies in its simplicity. It is quick, recognizable, and universal, capable of synthesizing emotion, critique, and humor in a single hand movement. From celebrities to ordinary citizens, the gesture traverses the century and integrates into the global informal language.

Despite being widely recognized, the middle finger does not mean exactly the same thing everywhere. In some cultures, it is highly offensive. In others, it is merely a comedic gesture. In various regions of Asia and the Middle East, other gestures carry equivalent weight. This reinforces that body language is always shaped by geography, history, and social codes. The strength of the gesture lies not only in the raised finger, but in the intention attributed to it and in the interpretation each society gives to its symbolism.

One of the reasons for the gesture’s longevity is its ability to navigate between humor and critique. From Aristophanes to today’s memes, the middle finger has been joke, protest, challenge, catharsis, and satire. It appears in film scenes to mark irony, on magazine covers to provoke debate, and in political protests to amplify outrage. It is simultaneously a human gesture and an expressive instrument. It can be rude, but it is also language. It can be offensive, but it is also iconographic. Few gestures carry such duality.

In the 21st century, the gesture gains new life. It becomes an emoji, GIF, sticker, meme, pop symbol, and graphic element in campaigns. It digitalizes without losing potency. Irony crosses screens and finds new audiences who reinterpret it daily. Thus, the gesture that was born in Greek comedy and traversed empires transforms into a global cultural product. It survives because it is direct, recognizable, and oddly universal. Technology has only amplified its presence.

The history of the middle finger reveals something essential. Gestures also tell stories. They carry cultural layers, emotions, tensions, and narratives that endure over time. Today, the gesture provokes laughter in some, irritation in others, and reflection in many. It endures because it is human, expressive, and contradictory. And it is precisely this combination that ensures its permanence in culture.